Until the past week spring has been slow to arrive in New England. As an antidote, I have spent time reorganizing images and virtually revisiting gardens and parks I photographed during the past year. On a day trip to Richmond, outside of London, I rented a bicycle and rode along the Thames with the intent of photographing Richmond Park. Along the way I visited the garden at Ham House.

Described by the National Trust as “the most complete survival of 17th century power and fashion,” Ham House stands in the midst of a garden within a garden. The ensemble is most often described as majestic.

With verdant lawns, ancient trees, topiaries, terraces, kitchen gardens and a wilderness replete with structures perfect for clandestine rendezvous, the gardens design and survival are linked to a powerful and politically savvy woman, Elizabeth Murray (1626 – 1698), Countess, Duchess and often described as “more than a friend” of Oliver Cromwell.

Ham House was built by Thomas Vavasour, a naval captain. In 1626 it was acquired by Scotsman William Murray who later bequeathed it to his daughter, Elizabeth. William was close to Charles I and shared his taste in architecture and art. Forced to flee during the Civil War of 1649, it is Elizabeth who is credited with preserving the property until Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660.

ELIZABETH MURRAY, COUNTESS OF DYSART, DUCHESS OF LAUDERDALE, IN HER YOUTH (1626-98) by Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), painting in the Duchess’s Bedchamber at Ham House, Richmond-upon-Thames.

©National Trust Images/John Hammond

A woman of many talents, Elizabeth is described as complex, ruthless, and charming. In the 1906 Book of English Gardens, by M.R. Gloag is a quote about Elizabeth attributed to Bishop Burnett that opines, “She was a woman of great beauty, but far greater parts; she had a wonderful quickness and an amazing vivacity in conversation; she had studied, not only divinity, history but mathematics and philosophy. She was violent in everything, a violent friend and a much more violent enemy.”

In 1672 shortly after the death of her first husband, Elizabeth married the Duke of Lauderdale. A power couple extraordinaire, they traveled widely and spent lavishly, improving Ham House and expanding its gardens.

Miraculously, both were little affected by changes throughout history and emerged relatively intact into the modern era. Like Rapunzel, they “slept” through most of the 19th and 20th centuries until 1948 when they were given to the National Trust of Britain.

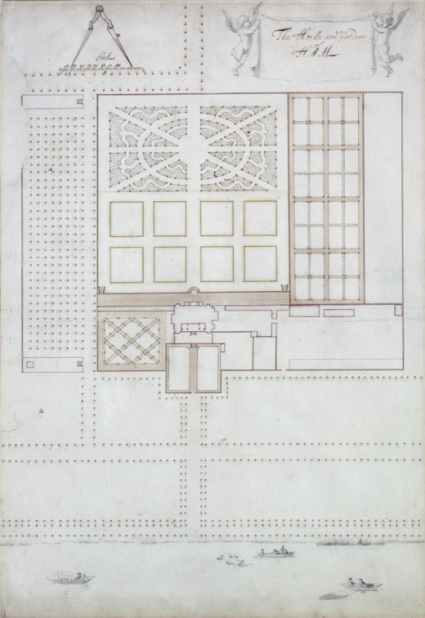

The plan below by Slezer and Wyck is dated 1672 and while it may not have been fully realized during Elizabeth’s lifetime it was used by the National Trust as a framework to restore the gardens in 1975, using plants introduced in England before 1700. The plan depicts a formal axis connecting the river to the house and the house to its garden.

John Slezer and Jan Wyck plan for the garden, c.1671-2, in the Library Closet at Ham House, Richmond-upon-Thames.

©National Trust Images/John Hammond

In 2011 the National Trust commissioned artist and illustrator Louise O’Reilly to create an artist’s book about the 17th Century garden at Ham House, in collaboration with historian Sally Jeffery, as part of the Interaction Programme for the Garden of Reason Project. The beautifully illustrated result utilizes historic plans and descriptions of the garden as well as documents from the archives dating from 1653 and 1698.

The plan below, from The Gardens at Ham House, is available online.

The following is a brief tour of the gardens. For additional information visit the Ham House and Garden website of the National Trust.

The Forecourt: The Forecourt is defined by a circular gravel path set in lawn with a sculpture of Father Thames at its center. Brick walls containing niches set with busts enclose the space (some of which has been replaced with a wrought iron fence allowing for more permeability). The formal and symmetrical setting of the forecourt is enhanced by clipped bay topiary of yew cones and box hedges.

The Cherry Garden: One of the property’s most iconic spaces, the Cherry Garden, in the north-east corner, contains triangular and diamond-shaped beds, enclosed with box hedges and cones filled with lavender and Santolina. A statue of Bacchus, the god of wine and the garden’s only original piece of sculpture, is at its center. Hornbeam tunnels, underplanted with clipped yew hedges, enclose the cherry garden which, according to O’Reilly and Jeffery, was in use when Elizabeth was at Ham House. In 1653 eighty-four cherry trees were identified as being planted here. The current design is based upon the Slezer and Wyck plan of 1671.

The South Terrace: Providing a viewing platform from which to enjoy the garden, the gravel terrace retains the characteristics of the 1671 plan. A herbaceous border, framed by an evergreen hedge, runs along its length, providing seasonal color. During the summer months orange and lemon trees are placed here.

The Plats: Comprising eight grass squares, the plats are visible in the Slezer and Wyck plan and were reinstated by the National Trust in its 1975 restoration. The pathways provided an ideal venue for strolling and enjoying outdoor entertainments.

The Wilderness: In contrast to the plats the wilderness, which contains sixteen compartments, is densely planted with hornbeam hedges and field maple, providing an opportunity for privacy. Grass paths, laid out in a pattern loosely resembling the Union Jack, connect to four summerhouses providing additional opportunities for respite and concealment.

Kitchen Garden and Orangery: Occupying the south-west corner of the garden, the kitchen garden was redesigned in 2002-2003 based upon the Slezer and Wyck plan. The Orangery was built in 1674 and may be, according to the National Trust, one of the earliest surviving structures built for this purpose. The orange, lemon and pomegranate trees which were placed on the south terrace overwintered here.

Today the refurbished structure houses a café that features produce from the kitchen garden.

The image of the Orangery below, by Katherine Montagu Wyatt, is from A Book of English Gardens which contains a romantic description of the property from the turn of the century, predating the garden’s restoration.

Among other observations in A Book of English Gardens is the rich and verdant beauty of the riverside setting surrounding Ham House, which is enhanced by stately trees and greenswards. Although I did not photograph what is described as The Melancholy Walk, there remain formal avenues of trees (or the reminders thereof) both within and outside of the property providing a palette of textures and multi-hued shades of green that adds to the elegance of the setting.

Copyright © 2015 Patrice Todisco — All Rights Reserved

Wow, that was so fun to read your post. I would love to visit Ham House my self sometime when the gardens are looking as lovely as they do in your photos. Thanks so much for sharing your talents.

It’s an easy visit from London and you can walk (or ride a bike) there from Kew.